Old translator, new home

Over the years between 382 to 405 CE, a scholar called Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus, also known as Jerome of Stridon, worked on a translation of the Hebrew bible into Latin. His translation became known as the Vulgate Bible. History remembers him as Saint Jerome, the patron saint of translators, librarians and encyclopedists.

Over the years between 382 to 405 CE, a scholar called Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus, also known as Jerome of Stridon, worked on a translation of the Hebrew bible into Latin. His translation became known as the Vulgate Bible. History remembers him as Saint Jerome, the patron saint of translators, librarians and encyclopedists.

Throughout the Catholic church Latin was the language in which God spoke and his word was transmitted until the medieval period, when calls began for translations of the bible into other languages.

Individual names are associated with the translations.

Whilst Martin Luther is rightly remembered as a seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation and scissions from the Church of Rome, he was also responsible for the translation of the bible into German, which had a tremendous impact on both the church and German culture, including fostering the development of a standard version of the German language. In the English-speaking world, whilst the first authorised version of the bible in English – the King James Version – was compiled by a committee, the overwhelming majority of the text used was in fact translated the best part of a century earlier by William Tyndale, who was executed in exile in Vilvoorde in what is now Belgium in 1536.

In those and earlier times many biblical translators were accused of heresy, a convenient crime against religion.

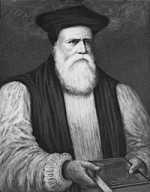

One bible translator who did not share Tyndale’s fate was William Morgan (c. 1545 – 1604), Bishop of Llandaff and of St Asaph, and the translator of the first version of the whole Bible into Welsh from Greek and Hebrew.

One bible translator who did not share Tyndale’s fate was William Morgan (c. 1545 – 1604), Bishop of Llandaff and of St Asaph, and the translator of the first version of the whole Bible into Welsh from Greek and Hebrew.

The bible in Welsh was the gift of Elizabeth I to Wales and went some way to redressing the crass colonialism of her father’s actions in 1536 when legislation was enacted that made important changes in the government of Wales.

Wales had previously been annexed – i.e. colonised – by the 1284 Statute of Wales, also known as the Statute of Rhuddlan. This introduced English criminal law to Wales, but Welsh custom and law were to operate in civil proceedings.

Henry’s new act declared the king’s wish to incorporate Wales within the realm. One of its main effects was to secure “the shiring of the Marches”, bringing the numerous marcher lordships within a comprehensive system of counties . Another of its effects was to introduce uniformity in the administration of justice. However, the latter entailed English being the only language of the courts of Wales. This meant that Welsh-speaking defendants appearing before the courts were dished up “justice” in a language they did not understand in proceedings in which they were unable to participate.

Furthermore, Henry’s legislation also decreed that those using the Welsh language were not to receive public office in the territories of the king of England.

Anyway, with the background out of the way, let’s get back to Bishop Morgan and his bible in Welsh.

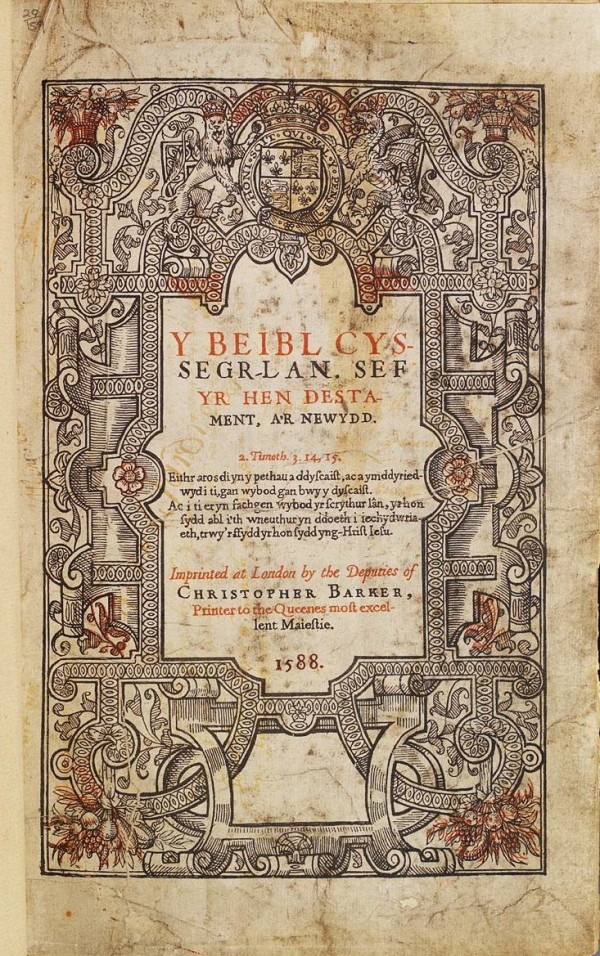

Morgan was a student at Cambridge when leading Welsh Renaissance scholar William Salesbury published his Welsh New Testament in 1567. Whilst he was pleased that this work was available, Morgan firmly believed it was important that the Old Testament also be translated into Welsh. Morgan’s work on his own translation of the Old Testament commenced in the early 1580s and this, together with a revision of Salesbury’s New Testament, was published in 1588.

The Welsh bible is dedicated to Queen Elizabeth I (English translation of dedication here). Elizabeth, a fervent Protestant, is said to be a firm supporter of the introduction of the Welsh bible in Wales as she believed it would help spread Protestantism in Wales at the expense of Catholicism.

Morgan’s translation also allowed a highly monoglot Welsh population to read and hear the Bible in the vernacular for the first time. In the long run, the Welsh Bible saved the language from possible extinction.

If readers are by now asking why your ‘umble scribe has bothered to write several hundred words on religion, politics and history in Wales, may I refer readers back to this post’s title.

There are very few public memorials to translators (leaving to one side all those medieval painting of St Jerome in caves of varying levels of comfort. Ed.). One of these – of William Morgan himself – has just been installed in one of his old benefices, according to the Powys County Times. A decade ago sculptor Barry Davies created an oak statue of the Bishop which formerly stood outside the Public Hall in Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant. The 7 foot tall statue has now been moved inside the parish church of St Dogfan by a team of local farmers, supervised by Mr Davies.

The article states the following as the reason for the statue’s move:

The statute was commissioned 10 years ago as part of a lottery funded project in the village, but weather conditions had led to fears the statue could become damaged and so a decision to find an indoor home for the bishop was made.

Of the one thousand original copies of the first edition of Morgan’s Welsh bible produced, it is estimated that some 26 survive today. It was republished in 1620 and that edition was still in use as the standard Welsh bible until the 20th century.