New Conservative government descends on Westminster – picture exclusive

Any resemblance to the new Mad Max Fury Road film is purely coincidental.

Any resemblance to the new Mad Max Fury Road film is purely coincidental.

There’s a hidden exclusive in today’s online edition of the Bristol Post. Unknown to the fans and probably the club itself, the Post reveals that Bristol Rovers now play in “blue and white stripes“, as shown by the following screenshot.

![]()

For the benefit of passing Post journalists, here are the three strips currently used by Bristol Rovers. Please note the only stripes are on the alternative away colours and have one thin blue stripe. The pattern used on the regular strip is commonly known as “quarters“.

The Post also mentions in the article that Catalonia’s CE Sabadell FC (who are in the Spanish Segunda División. Ed.) play in a strip “similar” to that of Rovers. FC Sabadell’s current strips are shown below and yes, the home strips do look very similar, even if the teams’ respective league positions do not; Rovers are chasing promotion from the Conference, whilst Sabadell are fighting relegation.

Let’s hope the players of both teams are more on target than Bristol’s alleged newspaper of record. 🙂

The minions of the Bristol Post, possibly under strain from toiling away at the Temple Way Ministry of Truth looking for the city’s blandest news content, seem to have particular difficulty with homophones, i.e. words that are pronounced the same as another word but differ in meaning and may differ in spelling.

This was amply illustrated below by a photo gallery posted this morning on the local organ’s website.

Should the Post’s ‘journalists’ wish to cure themselves of acute homophonia, help is at hand up at Bristol University.

Its website has a handy grammar tutorial page for the illiterati on the simple differences between there, their and they’re.

To quote from that page

There is the place, i.e. not here.

Their is the possessive form indicating belonging to them.

They’re is the contracted form of “they are”.

Have you got that, Bristol Post, if so Bristol University’s site also has a useful exercise to check whether the lesson has sunk in.

Spotted this morning in the bowels of Bristol’s tawdry temple to consumerism, Cabot Circus.

In the words – and with the intonation – of the former editor of the Daily Telegraph, Bill Deedes: “Shome mishtake shurely?”

No further comment is necessary.

Saturday 28th March dawned grey and drizzly for the TidyBS5 Big Clean organised by Up Our Street and local residents.

For your correspondent it dawned even earlier; the alarm clock was set for 6.00 a.m. to ensure he was sufficiently awake to be interviewed down the line about TidyBS5 and the event on BBC Radio Bristol by their Saturday breakfast show presenter Ali Vowles.

However, the rain did not put off an amazing 33 people – including one PCSO from Trinity Road Police Station – turning up at Lawrence Hill roundabout at 11.00 a.m. to help remove litter from the area for a couple of hours. Indeed, such a number of participants was so unprecedented that more litter pick equipment had to be ferried down from the Up Our Street Office.

Also amongst the hardy souls who turned up was a contingent from the Good Gym, which takes exercise out of the gym. Members runs to a venue, help a local community project and then run back. Your ‘umble scribe is very pleased we attracted their support.

Local councillor Marg Hickman also attended to show her support. Wouldn’t it be good if we could get Bristol Mayor George Ferguson to turn out for the next one and put some physical effort into Bristol’s year as European Green Capital? 😉

After receiving safety instructions (avoid picking up broken glass, no needles, etc. Ed.) we then scattered to various sites around the area to get work.

Areas cleaned included:

A fantastic amount of rubbish was removed and collected later in the weekend by Bristol City Council.

Well done and many thanks to all who took part.

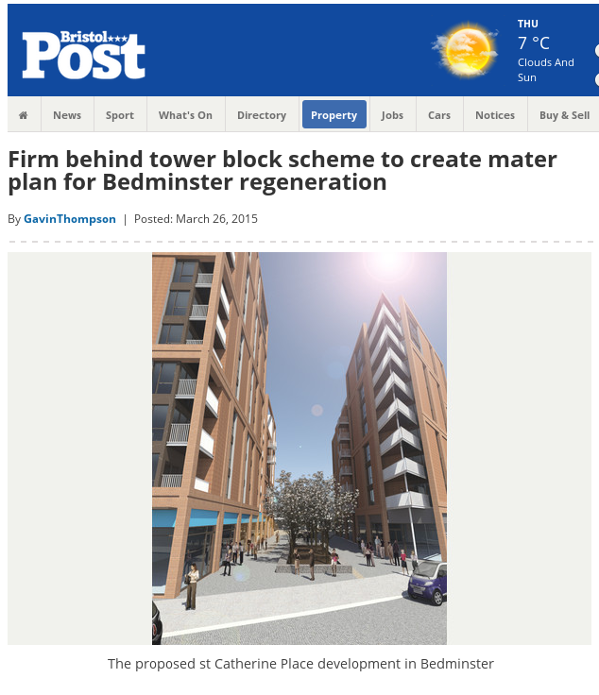

Today’s Bristol Post carries a piece by Gavin Thompson about the activities of property developers in Bedminster that has a novel twist – a maternal blueprint – as shown by the screenshot below.

Bedminster has so far escaped the worst attentions of property developers who’ve been allowed a very free hand by Bristol City Council to wreck the city’s outstanding heritage with cheap and nasty modern developments, as is happening currently on the site of the Ebenezer Chapel in Midland Road in St Philips (posts passim).

One consequence of the current media focus (which continues today, with the Mirror describing his tactics as “sleazy”. Ed.) on the business activities of Conservative Party Chairman Grant Shapps (right) has been a linguistic one.

One consequence of the current media focus (which continues today, with the Mirror describing his tactics as “sleazy”. Ed.) on the business activities of Conservative Party Chairman Grant Shapps (right) has been a linguistic one.

Many people have rediscovered a word which came to prominence during World War 2 – spiv.

This word has often been used by those commenting on online articles on Shapps’ dubious business activities to describe the man himself.

Oxford Dictionaries defines a spiv as:

A man, typically a flashy dresser, who makes a living by disreputable dealings.

During World War 2 those disreputable dealings usually meant that spivs circumvented the strict rationing regulations and/or could procure commodities or items that were hard to get.

The spiv was personified during my younger years by Private Joe Walker (left) in the TV comedy Dad’s Army. Walker was played by actor James Beck, who died suddenly at the age of 44 during production of the programme’s sixth series in 1973. In the series, Walker is a valuable asset to the platoon, due to his many “business” connections and his uncanny ability to conjure up almost anything that is rationed or no longer in the shops due to the war – and he will also have it in vast supply (for a price).

The spiv was personified during my younger years by Private Joe Walker (left) in the TV comedy Dad’s Army. Walker was played by actor James Beck, who died suddenly at the age of 44 during production of the programme’s sixth series in 1973. In the series, Walker is a valuable asset to the platoon, due to his many “business” connections and his uncanny ability to conjure up almost anything that is rationed or no longer in the shops due to the war – and he will also have it in vast supply (for a price).

For a generation older than mine, the spiv was perhaps characterised by comedians such as Arthur English (right), whose usual persona in the early days of his career was a stereotypical wartime “spiv”. As a consequence of this persona, Arthur English became known as “The Prince of the Wide Boys” (meaning in this context a man who lives by his wits, wheeling and dealing. Ed.). Wide boy is also a term that could possibly be applied to Shapps as an alternative to spiv.

For a generation older than mine, the spiv was perhaps characterised by comedians such as Arthur English (right), whose usual persona in the early days of his career was a stereotypical wartime “spiv”. As a consequence of this persona, Arthur English became known as “The Prince of the Wide Boys” (meaning in this context a man who lives by his wits, wheeling and dealing. Ed.). Wide boy is also a term that could possibly be applied to Shapps as an alternative to spiv.

As regards the origins of spiv, there are several possibilities.

Oxford dictionaries reckons it originates in the 1930s and is perhaps related to “spiffy“, meaning “smart in appearance”, which dates back to 19th century slang in this context.

Another possibility is that it’s related to “spiff“, a bonus for salespeople (especially for drapers but later for car salesmen, etc.) for managing to sell excess or out of fashion stock. The seller might offer a discount, by splitting his commission with the customer. A seller of stolen goods could give this explanation for a bargain price.

Yet another suggested origin is that it comes from the nickname of Henry “Spiv” Bagster, a small-time London crook in the early 1900s who was frequently arrested for illegal street trading and confidence tricks. National newspapers reported his court appearances in 1903-06.

Furthermore, it has been speculated that it is VIPs backwards. In addition, further speculation has it that the word was also a police acronym for Suspected Persons and Itinerant Vagrants.

Finally, there are also hints that it could have been borrowed from Romany. In that tongue, spiv is a word for sparrow, implying the person is a petty criminal rather than a serious “villain”.

Today this blog can reveal exclusively that the much-maligned Bristol Post has discovered time travel. This was shown by an item published today, 20th March, entitled “Seven things to do in Bristol tomorrow, March 17“.

I’m now waiting for the follow-up article from the Post detailing how I can travel back in time to do those aforementioned seven things. 🙂

Hat tip: Redvee.

The Bristol Post is not immune to the odd error every five minutes or so and today is no exception, as is amply demonstrated by the screenshot below of an item from today’s online edition.

Even the image tag’s alt attributes include the wording “A day on the beach at Weston-super-Mare”.

If Weston beach has been covered in tarmac and is now reserved for use by motor vehicles, I do hope the highway engineers built it well above the high water mark for spring tides, which have a range sometimes in excess of 13 metres.

On the other hand, the Bristol Post does have form when it comes to writing the wrong captions for images on its website (posts passim).

My niece Katherine has recently posted a review of Old Kent Road, a documentary by Ian Parkin on her website.

The review is reproduced below by kind permission of the author.

I recently watched ‘Old Kent Road’, a new documentary film written and directed by Ian Parkin. The screening took place in Deptford Cinema, a new not-for-profit space which has recently opened on Deptford Broadway.

The synopsis of the film states the director’s intentions: ‘(to) explore the rich history, examine its pluralist architecture and take stock of what the road is now.’ I was expecting the film to provide a historical background to the area, interlaced with local interviews and touching on the threat from property developers who have the road in their sights. Instead I was shocked by the bloody-minded ignorance of a film that bombards its audience with the director’s bigoted nostalgia.

The film starts with a summary of the road’s history, from its Roman origins and Saxon name of Watling Street, via Chaucer to Victorian Britain and the present day. This is the end of the historical background, and shortly afterwards the mood changes abruptly. Due perhaps to his hurried rendition of the road’s history, in which there is no gap between the Victorian era and our own, Parkin laments the transformation of the Georgian terraces and gardens into ‘gaudy’ shopfronts as if this was something that happened overnight. His ensuing statement about the road’s increasing poverty and deprivation seem to come from the same misinformed viewpoint.

Parkin goes on to complain about the lack of pubs and bars on the road (even though quite a few are shown in passing). He interviews three men about their recollections of the drinking culture in the area during the 1980s. What proceeds is a lengthy and jumbled summary of their nights out. Why the narrator spent so long interviewing them, despite their derogatory remarks about women and their dubious idea of ‘a good night’ (‘you start a fight, you get nicked, you pull a fat bird’) is unclear. The discussion was completely unedited, allowing the men to ramble on at leisure and completely killing any momentum that could have been building in the narrative.

Strangely, the interview stands out for being one of the few times in the film where the narrator himself paused for breath. Footage was rarely allowed to speak to itself, with no relationship between sound and image except that which we were force-fed by the commentary. There were times when this was morally questionable. Snooping on ‘migrants’ meeting in a Tesco car park, while making assumptions about them and their lives, or lamenting the poverty of the area while showing close crops of people’s houses and shopfronts is, frankly, criminal. Filmmakers have an ethical responsibility to the people and places they are depicting, and this film felt at times like a one man diatribe.

An example of this is when Parkin takes issue with the number of churches along the Old Kent Road. Instead of interviewing any churchgoers or members of the clergy, he prefers to film from a distance, while making a private mockery of each organisation. Churches are scorned for their ‘humorous taglines’ and supposedly inappropriate locations. One is criticised for using a building on an industrial estate, another for being ‘next to a Plumbase shop’. Some are blamed for taking buildings away from supposedly ‘better’ uses, for example the Iglesia la Luz del Mundo (Church of the Light of the World) which is lambasted for having the temerity to occupy the former home of Regency architect Michael Searle. Even more bizarrely, another church is castigated for using the former Wells Furniture Emporium building. Parkin remarks on the seemingly astonishing coincidence that this building bears resembles to a traditional church. But, he says, as the building was not built as a church, ‘the light that shines in this building is despite the use, not because of it…it is a secular light’.

This is a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of space, and one of the main problems with the film in general. Buildings and spaces do not have inherent qualities that are present from their birth. These come with a building’s social use, the patterns and activities of the people and groups who use them. Searle’s house is no good to the public as an empty relic, and the bakelite brilliance of the Wells building seems perfectly suited to its new use. Similarly, empty buildings do not magically retain their former qualities. Later in the film, Parkin looks to two empty buildings on the road, which have had mock signs installed to make them look like shop fronts. He praises the fact that these buildings are empty, and says we should admire them, because ‘at least they haven’t been gentrified yet’. These buildings are not worthy of praise simply because of their age. Parkin seems to want to treat them as relics, with their peeling paint and crumbling brickwork. But this, together with the word ‘gentrified’ is precisely the type of thinking that allows property developers to take over. It implies that gentrification is a homogeneous, inevitable process in which we, as local residents, have absolutely no say. Though the situation appears bleak, the idea that any new use for a building is automatically harmful (what about converting it into social housing, or a new community centre?), and that they are simply waiting to be pounced upon by the likes of Lend Lease or Brookfield, is a complete fallacy. If we stand by and simply admire such buildings in their derelict or dilapidated state, we are simply asking for the developers to snap them up.

These big development companies are barely mentioned, besides a few comments at the end which seem tacked on for good measure, without any critical focus. Existing large developments are equally absent, except the ‘Walkie Scorchie’, everyone’s favourite coffee-table joke, and a brief section about the Shard in which it is described as ‘a lighthouse standing proud’. Parkin does criticise the Shard’s architecture and the lack of a coherent skyline in the City, but the fact that such a monument to oil-baron investment and free market Capitalism can be compared to a guiding beacon is very worrying. What about the tactics of the big property developers that allows them to build such megaliths, and what does it mean for areas like the Old Kent Road? If Parkin had focused his attentions on the motives of such big companies and how they are able to take over an area, the film could have been very different. The Old Kent Road has undergone a great many changes in its recent history, now with large supermarkets and out-of town shopping centres catering more to passing motorists than the surrounding community. But this is due to the skewed policies of successive Governments, who have been sitting comfortably in the back pockets of large corporations since the 1980s. This partnership between politics and big business is where we should lay the blame for the increasing privatisation and homogenisation of our towns and cities, not the people who live in and use them.

After all that is said in the film, its rather weak ending of ‘let’s enjoy the Old Kent Road now as it is, before it changes’ seems totally out of place, not to mention disingenuous. Parkin uses the film to pour his white-middle-class-male scorn over the road and its inhabitants. This narration-heavy style of filmmaking can be dangerous, as it allows people to ram their own prejudices down viewers’ throats, without recourse to self-reflection or a second opinion. Parkin has neglected his ethical responsibility in making this film. He also leads us to believe that the encroachment of transnational property developers is totally inevitable, and therefore above discussion or debate. This is especially dangerous as the film is billed as an ‘alternative’ history of the area, and if left uncriticised it could do a lot of damage.